The monograph below (a monograph is essentially a very long academic journal article) is both long and covers 1500 years of history -- and since both history and long articles tend not to be read, I think I had better summarize quickly what it says. It says: There has always been in Anglo-Saxon politics a major opposition between those who want to extend central government power and those who want to preserve individual liberties; Conservatives have been for the most part the chief repository for the individual liberties cause; Conservatism is a cautious psychological syndrome rather than a philosophy; That syndrome does naturally and strongly lead to both a respect for tradition and a policy preference for individual liberties. If you disagree with any of that, you had better keep reading

The historical origins and modern psychology of Anglo-Saxon conservatism

By John J. Ray (M.A.; Ph.D. -- version of late 2018)

"Law, language, literature-these are considerable factors. Common conceptions of what is right and decent, a marked regard for fair play, especially to the weak and poor, a stern sentiment of impartial justice, and above all a love of personal freedom . these are the common conceptions on both sides of the ocean among the English-speaking peoples.

-- Winston Churchill's view of what characterizes people of British descent both at home and abroad

Conspectus

This monograph relies on one authority and one authority only: The authority of history. But I think it may be useful if I pull together at the beginning what I think history teaches us:

Left-leaning psychologists and other Leftist "thinkers" sometimes "study" conservatism -- usually with the obvious motive of proving a theory which discredits conservatives in some way. But the shallowness of their actual knowledge of conservatives is shown when they feel the need to consult dictionaries just to find out what conservatism is (e.g. Altemeyer and Wyeth). That is a remarkably desperate recourse. Dictionaries record usage but they cannot tell you whether the usage is right or wrong, shallow or profound. They even record mistaken usages.

The problem underlying the recourse to dictionaries is that the Leftist wouldn't know conservatism if he fell over it. His only concept of conservatism is the caricature of it that circulates in his own little Leftist bubble. But he does realize dimly that he doesn't know what it is. So with a schoolboy level of sophistication, he turns to his dictionary to find out what it is!

By contrast, in my studies of Leftism, I feel no need to rely on dictionaries. From many years of reading Leftist writings, I can tell you what Leftism regularly is. The essential element of Leftism is the desire to change society. That DRIVES Leftism. And society is people. So What the Leftist does or tries to do is to stop people doing what they want to do and make them do things that they don't want to do. They are not alone in that but that underlies all that they do and say. What changes they want and why they want them is also a big part of the story and I consider that in detail elsewhere. So conservatives tend to allow the natural world to continue on its way while Leftists forge an inherently unstable world that can be held together only by coercion. Leftism is quintessentially authoritarian.

The redirection of a large slice of people's spending power via compulsory taxation is only one part of the coercion. There are also many direct commands and prohibitions. The very expensive "mandates" of Obamacare were under much discussion in late 2013. Only a Leftist would think that old ladies should be forced to pay for obstetric care.

It may be noted that some people with strongly-held religious views tend to be like Leftists in trying to forge an unnatural world. That helps to explain why Leftists are infinitely tolerant of Muslim Jihadis and why the major churches tend to support the Left, some of them being very Leftist. In the 2004 Australian Federal elections, the leaders of ALL the churches came out in favour of the (Leftist) Australian Labor Party. The only exception was a small Exclusive Brethren group in Tasmania who supported the conservative coalition -- and their "intervention" sparked huge outrage in the media and elsewhere. (The conservatives won that election in a landslide).

And in England it is sometimes now held that "C of E" stands for "Church of the Environment", because of the Church of England's strong committment to Greenie causes. Cantuar Welby's scolding of business might also be noted. And a previous Cantuar (Carey, a generally decent man) called his little grandson "pollution" on Greenie grounds. Pity the children! And, in stark contrast with the Bible, a senior Anglican cleric has called "homophobia" a sin. The C of E and most of its First World offshoots no longer have strong feelings about salvation but they have strong feelings about Green/Leftist causes.

Because they focus so much on personal feelings and the promise of salvation rather than on "the world", American evangelicals are something of an exception but, even there, 10 million evangelicals voted for Al Gore in the year 2000 American Federal elections.

But back to conservatism: While conservatives tend to let the natural world run its course, that is not a defining characteristic. Nor is opposition to change a defining characteristic. What drives conservatism is something quite different.

What Leftists find in their dictionaries is that conservatives are opposed to change. That is indeed the prevailing Leftist conception of conservatives but it ignores one of the most salient facts about politics worldwide -- that conservative governments are just as energetic in legislating as Leftists are. Both sides busily make new laws all the time. And the point of a new law is to change something. The changes that Left and Right desire are different but both sides push for change. On the Leftist's understanding of conservatism, a conservative government that wins an election should do no more than yawn, shut up the legislature and go home until the next election! What conservatives mostly do, however, is reverse Leftist initiatives and STRENGTHEN existing social arrangements rather than tear them down. Both Left and right want change but WHAT changes they want are very different and very differently motivated.

What has happened is that Leftists are so self-righteous that they can rarely accept that conservatives oppose Leftist policies on the merits of those policies. So they have successfully put about the defensive myth that conservatives are opposed to ALL change, regardless of its merits. But those busy conservative legislators put the lie to that towering absurdity. Conservatives have NO attitude to change per se. It is Leftists who do. They long for it.

So in a thoroughly anti-intellectual style, the Leftist ignores some of the most basic facts about politics. That sure is a weird little intellectual bubble that he lives in. EVERY conservative that I know has got a whole list of things that he would like to see changed -- usually reversals of Leftist changes. But Leftist intellectuals clearly just doesn't know any conservatives.

So what really is conservatism? I have taught both sociology and psychology at major Australian universities but when it comes to politics my psychologist's hat is firmly on. One can understand conservatism at various levels but to get consistency, you have to drop back to the psychological level. And at that level it is as plain as a pikestaff. Conservatives are cautious. And that is all you need to know to understand the whole of conservatism.

In science, however, explanations just generate new questions and, as a psychologist, I am interested in dropping down to an even lower level of explanation and asking why conservatives are cautious. And I think that is pretty obvious too. It is in part because they can be.

As all the surveys show, conservatives are the happy and contented people. And with that disposition, conservatives just don't feel the burning urgency for change that Leftists do. Leftists cast caution to the winds because they want change so badly. ANYTHING seems better to them than the existing arrangements. Conservatives don't have that compulsion. Leftists are the perpetually dissatified whiners whereas conservatives can afford to take their time and get things right from the outset.

And why does that difference in happiness exist? As the happiness research often reminds us, your degree of happiness is inborn and, as such, is pretty fixed. Leftists are just born miserable.

So we have now dropped down into a genetic level of explanation. And we can at that level even derive and test a hypothetico-deductive prediction. If conservatives are happy and happiness is genetic, then conservatism should be genetic too. And it is. As behaviour geneticists such as Nick Martin have shown, conservatism has a strong genetic component -- which suggests that some people are just born cautious. It is, of course, no surprise that caution and happiness go together. See also here: "Researchers say our genes shape our political views"

So I think I have now gone as low as I can go in explaining conservatism. There are of course even lower levels of explanation possible (tracing the brain areas involved, studying the DNA) but our understanding of those levels of function is so far so crude that anyone purporting to offer explanations at that level is merely speculating.

But let me speculate anyhow:

A neurological explanation

Is there an inverse relationship between caution and emotionality? I think it stands to reason that there is. Emotion can easily make you throw caution to the winds and you need to be pretty level-headed to be cautious. Caution is about thinking ahead and weighing up the possibilities. And that requires cool reflection. You cannot reasonably do that in the heat of emotions

And that explains something about the Left-Right divide. Conservatives have always characterized themselves as cautious -- as wary of rushing into things -- whereas Leftists are clearly in the grip of strong emotions and throw caution to the winds. I think we can show that Leftist beliefs and policies make no rational sense but they do make emotional sense. An example of emotionality that any conservative blogger will be familiar with is the choleric rage that Leftists hurl at him or her in the form of emails and online comments. By contrast, conservatives are less emotional and are thus able to provide an anchor of rationality to public discourse.

The Leftist obsession over equality can only be called a passion. Equality between different people has never happened, cannot happen and will not happen. But a push for equality pervades Leftist thinking and policy. And Leftist are prepared to break heads to achieve their aim of equality. From the French revolution to Soviet Russia and Maoist China they slaughtered millions in support of the deeply felt need for equality that they obviously felt.

Soviet Russia was in fact grossly elitist. Only the Nomenklatura had access to living standards that were normal in the West. The rest of the population lived very restricted lives with abysmal accommodation and very limited choice of food and clothing. Even mass murder could not carve a path to equality. But Russian Leftists were prepared to go to that length to achieve it.

And global warming is another belief that can only be explained by an emotional commitment. The correlation between global temperature and CO2 levels has repeatedly been shown to be zilch yet Leftists still believe that CO2 causes warming.

And, of course, conservatives are often amazed by the way in which no presentation of facts can budge the beliefs of a Leftist. You can't reason with emotions. A Leftist's beliefs serve his emotional needs so a presentation of facts that challenge that belief is met with anger rather than interest. So the conservative habit of opposing Leftist beliefs with facts is futile. In doing that, one is challenging deeply felt emotional needs. The Leftist NEEDS to believe the crazy things he does in order to legitimate deeds and policies that he NEEDS to carry out.

What the emotions are will of course be variable. Many Leftist voters are presumably genuinely compassionate people who are so deeply moved by what they see as evils in the world about them that they will vote for ANY policy that purports to ameliorate the evil concerned.

Leftist leaders, on the other hand, may start out that way but because of their greater involvement with the issues concerned will either become wiser and swing Right (as Churchill and Reagan did) or will become bitter and angry at the impossibility of great change in the world's existing arrangements -- and will conclude that no progress towards the Good is possible until the whole existing system is smashed -- which is what drove the French and Russian revolutions. The Leftist becomes so frustrated at the impossibility of bringing about his dream world that he comes to hate the existing world and to be angry at those who enable or defend it.

So I predict that, if a good measure of emotionality can be devised at the neurological level, it will be shown to differentiate the Left and Right well. Conservatives will be shown to have milder emotions that enable them to think things through while Leftists will be shown to be emotion dominated. And I am sure that there are degrees of both orientations and that both extremes are maladaptive. I have met Right-leaning people who are so emotionally insensitive that they are social misfits. And I have met very emotional Leftists who are a neurotic mess.

What about self-report measures of emotionality?

There are of course some existing self-report measures of emotionality but self-report measures of politically-relevant variables cannot withstand the characteristic Leftist talent for defensiveness, particularly the defences of compartmentalization and denial. Leftists are largely incapable of admitting anything dismal or adverse in their thinking. They usually cannot admit their anger and the bleak thoughts it inspires.

I found just that in my many years of research into attitudes to authority. I have probably done more published research on that than anyone else alive or dead. A liking for authority is definitional of Leftism, with Communist countries being the indubitable example of that. But even in Western countries it is Leftists who are the big advocates of more and more government control over practically everything we do. They need central power to bring about the changes they want.

Their latest craze is to cut off all reliable sources of electricity in the name of their global warming fantasy. But no-one in the modern world would voluntarily leave themselves without a reliable source of electricity. So the big problem for Leftists is that, left to themselves, people don't behave in the way that Leftists dream of. So they must be FORCED to do as the Leftist wants.

And only a very strong central government can achieve that. Leftism is intrinsically authoritarian. Mr Obama's declaration on February 16, 2008, that he wanted to "fundamentally transform" America was nothing if not authoritarian.

So in questionnaires about attitude to authority Leftists should show a distinct tendency to approve of authority, even a love of it. But they don't. I repeatedly found in my surveys that Leftists were no more likely to approve of authority than were conservatives. And the reason for that is plain. Authoritarianism has a bad name. Everyone knows about Communist brutality. So putting yourself anywhere in that league is resisted. If they are to have any credibility or popularity at all, Leftists have a desperate need to dissociate themselves from authoritarianism. So any liking for big authority has to be denied.

The denial is so strong and so fundamental that even social desirability indexes don't pick it up. Leftists genuinely believe that they are good people and don't think they are faking anything in claiming that. The evil side of their wishes is brushed aside into a compartment that they don't enter. They don't confront the viciousness of which they are capable. They desperately need to think well of themselves, as T.S. Eliot observed long ago. So self-report measures just don't work. My hypothesis can only reasonably be tested neurologically

There does seem to be real progress in an understanding of the brain so it's possible that my neuroloical theory above will one day be confirmed. I think I have shown that it explains a lot

Going up a level

So having gone down the levels of explanation, I now need to go up the levels of explanation too. What does being cautious lead to? It rather obviously leads to distrust: Distrust of the wisdom and goodwill of one's fellow man, both as individuals and in collectivities. In Christian terms, man is seen as "fallen" and ineluctibly imperfect.

But trust and distrust are matters of degree and conservatives are perfectly willing to give trust when it has been earned. So where ideas are concerned, conservatives usually trust only those ideas that have already been shown to work as intended or which extend existing successful ideas. Leftists, by contrast, trust and put into action ideas that "sound" right to them -- without bothering to test first whether their ideas really do generate the consequences that they envisage. They usually don't of course. Leftists are theorists extraordinaire. They have no use for Mr Gradgrind's "facts". That theory is useful only insofar as it is a good guide to facts seems to be beyond their ken.

The enthusiasm for "whole language" methods in teaching kids to read is an example of untested Leftist policy being implemented. It was widely adopted in the schools but worked so badly that most schools have now reverted to phonics -- the old "tried and tested" method.

And conservative caution leads to conservatives valuing stability generally -- because sweeping changes could well not work out well -- and usually don't. Leftists usually seem to think they know it all but conservatives know that they don't. So conservatives may want various changes but also want to proceed cautiously with change. They want "safe" change, change off a stable base -- a base that embodies what has worked in the past.

And the traditional conservative advocacy of individual liberty also stems from caution. It is highly likely that a tyrant won't have your particular interests at heart so you want to be free to pursue your own interests yourself. And in the economic sphere that is capitalism.

Why the vast gulf between Left and Right? Why do Leftists live in their own little bubble?

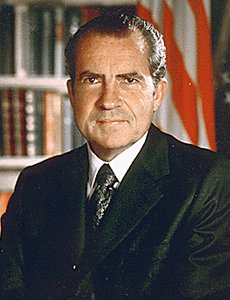

There is a famous anecdote about a journalist (possibly Pauline Kael) who was amazed at the election of President Nixon. "But I don't know anybody who voted for Nixon", she said. That bubble again. Wyeth, an Australian Leftist, spells out at some length how Left and Right seem to live in two different worlds, with very little communication between them. Wyeth does not know why, however.

I think the answer is obvious. I think that the separation exists because the Left has a reflex of closing its ears to anything it does not want to hear. They do that because their beliefs are so easily open to challenge. They cannot AFFORD to listen. Reality is against them. They have to invent a fictional mental world where, for instance, "all men are equal", despite the perfectly obvious fact that all men are different. All men are (allegedly) equal only in the sight of God -- and Leftists don't generally believe in him/her.

Global warming is a good example of reality denial too. It is agreed on both sides of the divide that the total amount of warming over the last 150 years has been less than one degree Celsius. Why is such a triviality worth notice? Leftists never say. Global warming scientists theorize that the warming might suddenly leap but that is mere prophecy -- and we know how successful prophecies generally are.

Conservatives, on the other hand spend most of their time in politics discussing and refuting Leftist arguments. Read almost anything on Townhall.com, for instance, and it will be discussing and refuting Leftist arguments and policies with appeals to the facts -- anything but ignoring them. By contrast, the fact that Leftists do NOT generally address conservative arguments is what makes them seem alien to conservatives. It makes them seem alien to rationality. Leftists very often mock conservative arguments in a superficial and cherrypicked way but that is a far cry from seriously working through them and honestly addressing ALL the relevant facts

Are conservatives "Right-wing"?

For the excellent reason that Right is the opposite of Left, opponents of the Left are commonly referred to as Rightist -- and that should be the end of the matter. But it is not. The problem arises from the expression "extreme right". What is "the extreme right"?

The answer to that has been greatly distorted by Leftist disinformation about Hitler. Hitler was by the standards of his day a fairly mainstream socialist. Even his ideas about "Aryans" were shared by such Leftist eminences as U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. But Hitler's defeat in war created a desperate need in Leftists to deny all that. So they invariably describe him as "right-wing" to deflect attention from the fact that he was in his day one of them. He was in fact to the Right of Stalin's Communism only -- so the Communist view of Hitler has been conveniently adopted by the Left generally. See here for full details about Hitler's ideas and background.

So Leftists tend to describe all tyrants and dictators as extreme Right on the grounds that their behaviour is like Hitler's. But all the great tyrants of the 20th century -- Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot -- were in fact Leftists so the various postwar tyrants should logically be called "extreme Leftists" -- though that's not logic that Leftists like, of course. It's only when a tyrant or a tyranny is clearly Communist (as in, for example, Peru, Nicaragua and Nepal) that Leftists will generally desist from calling the tyrant "Right wing". It would probably be most accurate to say that most tyrants are wingless: They believe only in their own personal power

So calling conservatives Rightists does little harm when normal everyday democratic politics is concerned but once we start talking about extremes of belief a large problem arises. Conservatives reject utterly the association with Hitler that Leftists try to pin on them.

There is clearly a lot of variation among postwar tyrants so presumably some are better examples of what Leftists call "right-wing" than others. The Latin American dictators seem to be prime candidates but what do we make of clowns like Idi Amin or democratically elected authoritarians like Lee Kuan Yew? Exactly WHICH dictators are good examples of "Right-wing" seems to be vague. Leftists appear to have no systematic thinking on that. So some lists include Fascists like Chiang Kai Shek, the monarchs of the Muslim world and even in some cases undoubted Communists like the Kim dynasty of North Korea.

So I too will have to leave vague just who is a good example of an "extreme Rightist". For the sake of looking at the subject at all, I will use "Hitler-like" or "Fascist" as a specification of what Leftists are talking about when they say "Right wing extremist" -- and leave it at that. I have however given separate coverage of the Latin American dictators further below. They have mostly been Bolivarists, a form of Fascism. And that Fascism is/was Leftist I set out at length here.

There are also of course a few individuals around in Western countries who are Hitler sentimentalists but they are so few and so unorganized that they are essentially irrelevant to modern politics. I do however have a discussion of them here.

Extremism versus stability: Taking things to extremes is the Leftist "modus operandi"

We are accustomed in political discussions to describe both ends of the political spectrum as "extremists". But what are the extremes? In the case of the Left it is easy: Communism. But what is an extreme conservative? The Left are sure that it is someone like Adolf Hitler but the logic of conservative commitment to individual liberty and suspicion of government makes libertarianism a much likelier extreme form of conservatism.

At this point I am going to skip forward a little, however, and say where I think people go wrong. I don't think there IS any such thing as extreme conservatism. Libertarians believe in a lot of stuff that conservatives reject. But I do believe that there is such a thing as extreme Leftism. How come?

I think that the whole polarity of politics is generally misunderstood. The contest between Left and Right is a contest between stability and the results of irritability/anger/rage. Conservatives are the sheet anchor of society. They ensure that there is some continuity and predictability in our lives. They are the anchor that prevents us all from being blown onto the shoals of arrogant stupidity in the manner of Pol Pot and many others.

For various reasons most people in society have gripes about it. Even conservatives can usually give you a long list of things that they would wish otherwise in the world about them.

But some of the discontented are REALLY discontented -- discontented to the point of anger/rage/hate -- and among them there is a really dangerous group: Those who "know" how to fix everything.

So the political contest ranges across a spectrum from valuing stability to various degrees of revolutionary motivation.

But can there be an extreme of valuing stability? In theory yes but I have yet to hear of ANY conservative-dominated government that lacked an active legislative agenda. BOTH sides of politics have changes they want to legislate for. Conservatives don't want stability at any price any more than they want change that threatens stability. So as far as I can see, ALL conservatives want change PLUS stability. And mostly they get that.

Pulling against that anchor that keeps society going on a fairly even keel, however, there is the Left -- who want every conceivable sort of change. Some just want more social welfare legislation and some want the whole society turned upside down by violent revolution. And the latter are indeed extremists.

So there is no sharp Left/Right dividing line -- just a continuum from strong support for stability amid change to a complete disrespect and disregard for stability among extreme advocates of change.

It is possible that there is somebody somewhere in the world who values stability so much that he/she want NO change in the world about them at all. If so, I have never met such a person. Everybody has gripes and change is a constant. The only question is whether we can manage change without great disruptions to our everyday lives. Conservatives think we can and should. Leftists basically don't care about that. For them change is the goal with stability hardly considered.

Now let me skip back to a question I raised earlier. I think we are now in a better position to answer that question. The question is why do conservatives and Leftists disagree over what extreme conservatism or extreme Rightism is? And the answer is now obvious. If it does not exist, no wonder people disagree over what it is. The theoretical inference would be that an extreme conservative wants ZERO change: he/she wants stability alone. But, as I have noted, such people appear not to exist and if they do exist they are surely too few to matter.

But what about the Leftist conviction that society is riddled by people like Hitler: "Racists" and "Nazis". Leftists never cease describing those they disagree with that way. Even a moderate and compromising Christian gentleman such as George Bush Jr. was constantly accused of being a Nazi during his time in office.

It is just propaganda. The Hitler interlude is the one bit of history they have heard something about and they know that Hitler was a very bad man and that racism in his hands was a very bad thing. So comparing someone to Hitler is a powerful form of defamation. And "ad hominem" attacks are a regular, albeit illogical, feature of Leftist argumentation.

Are the Japanese conservative?

In 2002, a reader, Derk Lupinek, who was living in Japan, sent me an email questioning my definition of conservatism. He said that my definition seemed irrelevant to Japanese politics. Here is what he wrote:

"I live in Japan, and when I first moved here I found myself trying to decide whether the Japanese were deeply conservative, as I had been led to believe, or whether they were actually quite liberal, especially given their attitudes toward sex.

They clearly do not value individual liberty, which would mean they are not conservative by your definition, but they seek to preserve their culture down to the most excruciating details, leaving me with the feeling that they are in fact deeply conservative, at least in the sense that Philosoblog intends.

So, while I do agree with your definition as it relates to conservatism in the West, it certainly doesn't account for deeply conservative individuals in other cultures, and those individuals are indeed trying to "conserve" something.

In other words, you seem to be using the term "conservative" to refer to a political movement that has occurred in the West, and Philosoblog is just using the term more generally to refer to a psychological mindset. Am I mistaken?"

I think I can now give a fuller reply than I did in 2002: I agree that "conservative" has come to have the lexical meaning of "opposed to change". And that is fine. I have no desire to re-write the dictionary.

But to understand what is going on we have to look at WHY conservatives oppose some changes. My point is that those individuals usually labelled "conservative" in the Anglosphere are motivated primarily by a love of liberty and that their opposition to what the Left want stems not from an opposition to change in general but from skepticism about the wisdom and benefit of Leftist policies, which are invariably authoritarian. Leftists want to stop us doing things we normally do and make us do things that we would not normally do, which is the irreducible core of authoritarianism

So, yes, the Japanese are conservative but they have different reasons for that -- reasons that I know little about.

So it is OK to characterize all conservatives, including Western conservatives, as being opposed to change -- as long as we do not take big mental leaps to say WHY they oppose some changes.

The claim that conservatives oppose ALL change is patently absurd Leftist propaganda. Notable conservatives such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Donald J. Trump are clearly energetic agents of change. Mr Trump seems to do just about everything differently. So by and large it is only the poorly thought-out ideas of the Left that conservatives rapidly reject. They have no attitude to change as such. They just don't want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

The people who DO have a particular attitude to change are the Left. Change is their entire message. They basically want to change everything -- out of an arrogant and ignorant assumption that they know how to create a new Eden. The Soviets even thought that they could create a "New Soviet man".

In 2019, the "Green New Deal" championed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez exemplified just how sweeping in scope and just how empty-headed Leftism can be. In good Leftist style, AOC wants to change just about everything in America. Sadly for America her ideas became hugely popular among American Leftists. She would create huge destruction given her way

The "New Deal" that the "Green New Deal" refers to was a series of economic initiatives in the 1930s by Democrat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that was modelled on the policies of Fascist Italy. Hillary Clinton's slogan in the 2016 presidential election -- "Better together" -- was also the central idea of Italian Fascism.

And there is always the unapologetic authoritarianism of "Bernie" Sanders:

He really has defended government bread rationing and he really does pledge that he will "transform the country"

Libertarianism versus conservatism

We occasionally see some rather poorly informed claims to the effect that libertarianism and conservatism are totally different -- e.g. an article by Walter Block here. I think therefore that a little clarification is required. The truth can be very simply put: Libertarianism is ONE ELEMENT in conservative thinking. More precisely, Libertarians and conservatives share an attachment to individual liberty.

Libertarians are in some ways like Leftists. Leftists tend to have very simple formulas for what is wrong with the world. Ask them and they will say: inequality, poverty and (more amusingly) intolerance. When you realize that leading Leftists are usually well-off and are totally intolerant of dissent, you can see how uninsightful and oversimplified leftist reasoning is. And aside from being mostly poor, libertarians are like that too. They oversimplify enormously: Get government out of the way and a new Eden will dawn.

Conservatives, on the other hand see everything as complex. They see that there can be other influences on human welfare than freedom. For instance, when a country seems threatened by foreign aggression (as Britain was in WWII) a conservative may see national security as an important consideration that may need balancing against individual liberty - hence conservative governments may introduce a whole range of "wartime measures" that reduce the liberties of citizens to some extent. Conservatives try to balance competing principles.

Another revelatory case is immigration. Since libertarians dislike governments and their restrictions, they usually favour open borders. If libertarians had their way, most of Mexico would end up in the USA. But conservatives see other issues as being involved -- such as pressure on welfare programs and other systems, and the importation of the dumb political ideologies that have kept most of the Americas South of the Rio Grande mired in poverty. What the immigrants have in their heads is important, not just the fact that they are a person. And conservatives also see it as a matter of property rights. If I have the right to say whom I will have living with me in my own home, surely groups of people (nations) also have the right to say who will live among them?

Libertarians also tend to ignore genetics. When proposing remedies for poverty, Leftists will say: "give the poor more money" while libertarians will say "Give the poor no money". Neither system will usually be practical so conservatives tend to say: "The poor ye always have with you". With no ideology to explain everything, conservatives can simply accept reality. As one of Britain's most prominent Conservatives recently said, some people are equipped mentally to do well and some are not. Leftists usually cry "racism" when genetics are mentioned so the conservative response is usually implicit rather than explicit these days. That people are born different underlies a lot of conservative thinking even though it can be risky to say that out loud.

Similarly with homosexual "marriage". Leftists see simply it as an equality issue, libertarians see it simply as a liberty issue while conservatives see it as impacting on many other things -- such as morality and the family and a general devaluation of marriage.

So conservatives try to align their thinking with the complexity of reality while libertarians have a "one size fits all" explanation and solution for all problems. Conservatives value liberty but don't think it is the answer to everything. And the only liberty Leftists value is your liberty to do what they say.

Freedom FROM

The rare rational Leftist with whom can have an intelligent discussion sometimes asks us advocates of individual liberty what we mean by freedom or liberty. They are right to ask that. Over the centuries men have often fought for freedom. But what was the freedom from? Scots often declared that they were fighting for freedom. So did that mean that they wanted a deregulated state? Not at all. What they were fighting for was freedom from rule by the English. That the Scottish king was at least as tyrannical as the English king did not bother them. They saw it as a plus to be tyrannized by a fellow countryman.

And we see a similar ambiguity among libertarians. It is sometimes said that there are as many versions of libertarianism as there are libertarians. Libertarians may even want opposite things. Some libertarians, for instance, want freedom for all individuals to smoke anywhere they happen to be. That is a pretty purist libertarian position but, fortunately, not one often adopted.

In contrast, another libertarian may value the opportunity for all people everywhere to be able to breathe air unpolluted by the stink of tobacco smoke. So the two libertarians may want opposite things but value both things in the name of liberty.

Examples like that show that there really is no such thing as liberty in the abstract. There are only freedoms from particular things. Liberty is meaningless without a predicate.

So to be frank and honest in our discourses we should list and justify separately what liberties we value. Calling oneself a libertarian contains no fixed meaning at all. A common list of things that libertarians want includes things that both Leftists and conservatives want but there will be no universally agreed list of those things. We need to justify each of those freedoms by themselves. Saying grandly that we stand for "liberty" is meaningless or at least uninformative. And the same goes for individual liberty. There is no such thing by itself.

There is probably a fair amount of agreement about what liberties advocates of individual liberty want but that is just true of one particular time and place and one particular culture. So being a libertarian is not easy at all. It provides you with no magic key to unlock the "correct" position on any issue. We need to argue each point of the liberties we want. Saying that we stand for freedom is just slipshod. There is in fact no grand value that we are standing behind. A love of liberty is always a love of some particular liberties.

Particularly under the influence of Disraeli, English conservatives often said that they stood for traditional English liberties -- which gave a reasonably clear list of liberties -- but there is not much left of those liberties in England these days. The modern British state is a bureaucratic and authoritarian monster.

Libertarians do specify in general what liberties they want. They say that they oppose force, fraud and coercion. Unpacking those generalizations into particular policies is the problem, however -- as I have shown above with the example of smoking.

Note: I use "liberty" and "freedom" interchangeably, which I think is common. One word originates from Latin and the other from German but that seems to be the only difference -- JR

Racism and some history of the changes in Leftist dogma

Before WWII, everybody was racist in the sense that they believed that racial differences are real and that some of those differences are more desirable than others. Both conservatives and Leftists agreed on that. And if they feel safe to say it, many conservatives still think that. I do.

But, exactly as I have pointed out above, prewar Leftists went a lot further than that. They carried their views to an extreme. They did not care how many applecarts they upset. They wanted either to breed out the inferior races (American progressives) or to exterminate them (Hitler). See here. Where conservatives just accepted a complex reality of long standing, Leftists KNEW what had to be done about it and so hurt a lot of people and did a lot of damage in the process.

When their old friend Hitler lost the war, however, Leftists had a desperate need to disavow all he stood for and so threw their whole rhetoric into reverse gear. They were still obsessed in their minds by race and racial differences but denied their previous destructive intentions towards other races. They now claimed benevolent intentions towards other races. Abandoning all interest in race was apparently beyond them. And in good Freudian style, they projected what they now disapproved of onto their opponents, conservatives. They accused conservatives of being what they still deep-down were. To see what's true of Leftists, you just have to see what they say about conservatives. They are too alienated from society to understand their fellow-man very well so they judge others by themselves

Leftist ostensible attitudes had flipped. But since conservatives had opposed Hitler and Leftism generally, conservatives for a long time just carried on with their existing moderate, balanced views. But for various reasons, what is moderate and balanced will change over time and conservative views do change to reflect that. Conservatives hold the middle ground. And while there is some change, there is also a lot of continuity in the middle ground.

For instance, a conservative today will most likely welcome Jews to his club where a conservative of the 1930s would not. But having separate clubs is hardly a major impact on civilization and the stability of society is not threatened in either case. Club membership and gassing millions are worlds apart in any objective evaluation of the matter

So in a sense Leftists are right to see that Hitler and conservatives have something in common -- some willingness to admit racial differences, for instance -- but are very wrong in their implicit claim that conservatives would carry such views to any kind of extreme. Extremes are for the Left -- not just theoretically but as a matter of historical fact. So Leftists are now as extremely anti-racist in their advocacy as they were once pro-racist. Conservatives by contrast just jog along trying to keep a firm hold on reality

So Leftists now say that what they once believed (until it became inconvenient) is "Rightist". Beat that!

Leftists take some generally accepted idea and carry it to extremes, hoping to be seen as great champions by doing so. Their extremism is a "look at me" phenomenon, a claim on especially great virtue. So whatever is conventional at the time will be something that leftists loudly champion, hoping to gain praise for doing so.

If it is eugenics that is a popular idea (as it was before the war) Leftists will energetically champion that. And they did up to WWII. Conservatives at the time also saw some sense in eugenics but did little or nothing to push it -- pointing out how eugenic policies would conflict with other values (Christian values especially) and could lead in unexpected and nasty directions.

Antisemitism is also a good example of how the Leftist decides on policy. Long before and up to WWII, antisemitism was virtually universal. Nobody liked the Jews and some degree of discrimination against them was normal and accepted. Not allowing Jews in your club was the commonest form of that.

So Leftists took antisemitism to extremes and became the leading critics of Jewry, culminating in the holocaust, which was the work of the National Socialist German Worker's Party. Leftists transformed minor discrimination into mass murder. Leftists don't present new ideas. They just push existing ones to extremes.. See here and here and below for more on that. Richard A. Koenigsberg, a psychoanalyst and long-time student of Hitler's record, also saw Hitler as not unusual ideologically:

In terms of the ideology Hitler put forth, he was not unusual. What Hitler did was to embrace and promote certain very popular, conventional political ideas—and carry them to a bizarre fulfillment.

When Hitler lost the war, however, antisemitism suddenly had bad associations so Leftists abandoned it forthwith and became, for a while, great champions of Israel. Democrat President Truman recognized the state of Israel within minutes of its being proclaimed and the Soviet Union was only three days behind him. Popular sentiment had changed so Leftists became energetic champions of the new sentiment.

The document above signed by Truman gives a vivid contrast to what his Democrat predecessor BEFORE the war did. FDR is of course well known for sending a shipload of German Jewish refugees (aboard the MS St. Louis) back to Hitler, rather than allowing them to disembark when they arrived at Miami.

For another example of "how we were" (or how prewar Leftists were) read the following from the Old Grey Lady (NYT) herself:

"In so far as Mexican immigration is concerned, it would be idle to deny the economic usefulness of Mexican laborers. But it is essential to face the fact that the great mass of Mexican immigrants is virtually not assimilable. For the most part Indian in blood, their traditions as well as standards of living are very different from ours." [Immigrants From The New World, Jan 16, 1930]

So the default meaning of "Right" or "Rightism" in the following essay will be: "committed to stability". That is only a minimum meaning, however. There is a lot more to conservatism than that. And I hope to present below extensive historical evidence to show what conservatism is and to show continuity in how conservatism works out in practice.

Flavors of Leftism

At this stage, however, I think I should flesh out my contention above to the effect that the beliefs that would be described by the Left as extreme Right are in fact just another flavor of extreme Leftism -- perhaps a broadly old-fashioned form of Leftism but Leftism nonetheles.

Leftists would decribe that identification as patently absurd. They would say say of the "extreme Right" that "they stand for everything we are against: antisemitism, capitalism, patriotism, eugenics etc."

That is a rather amusing list but before I go on let me introduce you to the People's Action Party, long-time rulers of Singapore. At first glance, the identification of the PAP as extreme Right would seem easy. They are arguably the most pro-business party in the world. They are a shining example of the economic triumph of capitalism. And they are also very authoritaraian, with strict limits on free speech and control of even minutiae of Singapore life.

So surely the PAP is a prime example of "far Right"? Just one niggling little detail, though. They were for many years a member of the Socialist International. Their origins are on the Left and their authoritarianism is what all Leftists try for -- as is the PAP's regulation of the private sector, activist intervention in the economy, and its welfarist social policies. And its self-identification as a "People's" party is in fact characteristic of the far-Left. And for a bit of color say what the party symbol below reminds you of:

Singapore is a long way from being Nazi but it illustrates that Leftism is a house of many mansions and that support for capitalism is no bar to being Leftist. The PAP was joined in that not only by Hitler but also by 20th century Sweden. And even the U.S. Democratic party gives at least lip-service to it when in campaign mode.

The PAP even has a eugenic program. It subsidizes and otherwise supports well educated women to marry and have babies.

And then we come to antisemitism. I feel I hardly need to say anything about Leftist support for antisemitism. It goes at least as far back as Karl Marx and, under the thin disguise of "anti-Zionism" is as virulent among the modern-day Left as ever. Truman represented only a short-term blip in Leftist antisemitism. So antisemitism is certainly no bar to being Leftist.

What about patriotism? Leftist intellectuals scorn it as a weakness of simple minds so can you be a Leftist and a patriot at the same time? Again I don't think we need to go far to answer that. The U.S. Democrats claim to be patriotic and the pompous challenge, "Are you questioning my patriotism?" always seems to come from Democrat politicians. Democrat patriotism does seem to be mostly a hollow charade these days but we only have to go back to the revered JFK to find it breathing unaided: "Ask not what your country ....". And the popular patriotic song "This land is my land" was written by Woody Guthrie, a Communist. And Stalin referred to his war with Germany as "The Great Patriotic war". Yes. you clearly CAN be patriotic and Leftist.

So there is nothing incongruous at all in identifying the so-called "extreme Right" as just another flavor of Leftism. Anybody who has had much to do with the far-Left will be aware of how fractious they are and the ice pick in the head that Trotsky got courtesy of Stalin is emblematic of that. Leftists can hate one-another at least as much as they hate conservatives and the rivalry between the "far Right" and the modern-day Left is sibling rivalry -- just as it was in the days of Hitler and Stalin.

So after that detour we can now go on to look at the full complexity of what actual conservatism is and why

The 19th century and Otto von Bismsrck

What I present below is an attempt to use history to define conservatism. And at the very least, I think you have to know something of the late 19th century to understand what has happened since then. So I am going to start this monograph somewhat in the middle of things rather than in the beginning or at the end. I do so because seeds sown in the 19th century have borne much fruit since. It was after all the era that produced Karl Marx, the most influential misanthrope of all times. But Marx was such an intellectual midget and such a depicable character (even his own father, the kindly Heinrich Marx, thought that Karl was not much of a human being) that it is no wonder his legacy has been so malign and, in the end, irrelevant. (If that summary of Marx seems too negative, a browse through the archives of my Marx blog should put any doubts at rest).

And insofar as Marxian politics were European, they lie outside the scope of what I attempt here. The conservative instinct does of course lead to different political policies in different times and places so I confine myself almost entirely to conservatism as it has developed in the English-speaking world. To a considerable extent, European conservatism is another beast altogether. As every conservative knows, however, simple, hard and fast rules serve us poorly in discussing human affairs so I am going to break my own rule immediately by looking briefly at a great European conservative. And a major reason why I mention him is because, like most great conservatives, he was also a major agent of change! The old Leftist slur that conservatives are simply opponents of all change has never been remotely true and it was certainly not true in the case of Otto von Bismarck. And who was it who said very publicly in the middle of the 19th century: "The past is buried...no human power can bring it back to life." It could have been any Leftist but it was in fact one of Europe's fiercest and most effective advocates of monarchy -- Otto von Bismarck. If that seems paradoxical, keep reading (and also see here).

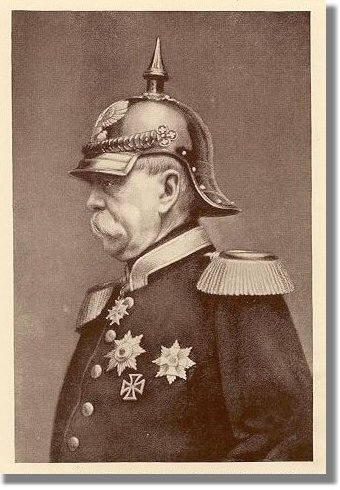

So, by contrast with Marx, the two greatest political figures of the late 19th century, Disraeli and Bismarck, were both great monarchists and devotees of their national traditions generally, and both achieved an enormous amount for humanity, peace and civility. Bismarck is normally pictured wearing his Prussian Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) -- though he was only in the reserves of the Prussian military in his glory years -- and that does tend to mislead people into thinking of him as a brutal militarist -- but that is the sort of ignorance you have to expect of people who have been fed the highly selective pap that passes for school history lessons these days.

Note that the Swedish military wear the Pickelhaube on ceremonial occasions to this day

Change of the Royal Guard at the Royal Castle Stockholm City, Sweden

In fact, for all his fearsome image, tough rhetoric and undoubted military achievements, Bismarck gave Europe a long era of peace and rapidly increasing prosperity.

After his great victory over Napoleon III at Sedan in 1870, one might have expected Bismarck to go on to a Bonapartesque quest to dominate all Europe, but he did nothing of the sort. A power-mad Leftist would almost certainly have done so but Bismarck was in European terms very much a conservative and, like American conservatives, his interest was in the welfare of his own country rather than in foreign adventures. The entire military campaign in France had not in fact been aimed at conquest at all. Bismarck simply used the war to unite all the German territories North of Austria under the Prussian crown. So when the war was over, all but a small German-speaking slice of French territory was evacuated and Bismarck concentrated on creating the nation that we now know as Germany -- not by force but by diplomacy -- albeit by diplomacy of a rather dubious sort at times. Very largely because of the great prestige accruing from the military victory that he had just engineered, he was rapidly successful. And a united Germany of course soon became the economic powerhouse that it has been ever since. But note this: from 1871 on, Europe had no major wars until 1914 -- a 43 year period of peace -- pretty unusual for Europe up until that time. And that long peace was largely Bismarck's doing. The united Germany's formidable military was as much a hindrance as a help because it made the rest of the world fearful and could well have encouraged a grand alliance against Germany. But by a series of ever-shifting and totally Byzantine diplomatic manoeuvres, alliances and treaties, Bismarck kept everybody off-balance and both Germany and the rest of Europe were left free to prosper peacefully and to develop the full fruits of the industrial revolution -- which they did mightily (though not without hiccups, of course). So Bismarck was instrumental in the great leap forward in prosperity that took place in the whole of Europe in the 19th century. Where Marxism and socialism breed at best stagnation, the cautious and pragmatic Bismarck created (or at least enabled) unheard-of rises in the standard of living in the whole of Western Europe.

Despite his success at ensuring international peace, Bismarck was not as successful at ensuring peace on the home front. As in most of Europe, the newly-created industrial working class was in a fairly ongoing ferment -- a ferment in which Marx played a small part. So there were some serious rebellions, uprisings and disturbances in Germany. As in foreign affairs, however, Bismarck's ever-shifting policies and alliances managed to keep the peace overall. Regrettably, however, it was a fragile peace and violent socialism still lurked just beneath the surface. So after Bismarck was gone it broke out again -- as the powerful Communist and Nazi movements of the post-1918 period.

Sir John Tenniel's famous 1890 cartoon on the centrality of Bismarck to continued order in Europe was both insightful and prophetic.

Dropping the pilot

I must reiterate, however, that there are large differences between the political Right in Europe and Anglo-Saxon conservatism. My reading has largely been confined to the latter but from what I have seen of the European Right, it is much more in favour of a powerful State, largely Catholic and more antisemitic. What the European Right seems to have in common with Anglo-Saxon conservatism seems mainly to be a high degree of realism, which leads in turn to a rejection of revolutionary change and a respect for private property and what has worked in the past.

And Bismarck was of course firmly in the European tradition. His determined and successful creation of a strong and unitary German State is only one example of that. Whilst Kanzler of Prussia, he did for some years rule Prussia solely in the name of the Kaiser -- in defiance of the Prussian parliament. In doing so, he certainly rooted his authority in the past but he was also acting in a way totally alien to Anglo-Saxon ideas of consultative government and the authority of parliament. His belief in State power also manifested itself in the now almost forgotten episode of his approach to Marx. Bismarck rightly perceived that Marx aimed at a powerful and all-controlling State and found such a magnification of the power of the Reich attractive. As a student of Marx and Marxism notes:

Towards the end of the 1860s Bismarck, with a view to cementing in place the Junker regime, toyed with the idea of massive nationalization of industry. This would reinforce the Reich and provide numerous sinecures to employ down-at-heel Junkers. He needed to pave the way for this 'one big trust' solution by re-engineering public opinion. He even offered Karl Marx the editorship of the Staatsanzeiger, the official organ of his regime. Karl Liebnecht's father William was to be given the editorship of Germany's main conservative daily. That both self styled revolutionists rebuffed the offers is frankly irrelevant, more important is that the offer was made in the first place

The 19th century in Britain: Disraeli

Across the Channel, however, there was a form of conservatism that was ultimately more successful. Bismarck's great English contemporary, Benjamin Disraeli, certainly presided over a great increase in British prosperity but, in addition, he was far more successful at containing domestic unrest. Like Bismarck he saw the need for worker-welfare legislation as a means of buying social peace and both men were notable welfare innovators -- THE welfare innovators, it might be said. So what was the secret of Disraeli's success? Fundamentally, it was sentimentality. Although he was always vocal about his own Jewishness, Disraeli had a sort of love-affair with the English people that was only surpassed in more recent times by the love-affair that Ronald Reagan had with the American people. And the results Disraeli got were arguably as transformative as the results Reagan got. Disraeli voiced a great love and respect for English traditions and preached the virtues of Englishness incessantly. And he included in his embrace the ordinary English working people -- whom he said were "angels in marble" -- people with great and good potential. He actually trusted the working-class -- an almost unheard-of idea among all the governing classes in Europe at that time. So he sponsored legislation that gave the workers the vote on a greatly increased scale. And they rewarded his trust by being far less susceptible to the political and social agitation that plagued their contemporaries in Europe. They developed a lasting trust in their national institutions that did far more for lasting peace and civility than anything else could have done.

Like many other politicians, Disraeli chopped and changed in his policies as he went through life (both Churchill and Reagan started out as liberals in their early years but ended up as luminaries of conservatism) and this has led to bitter denunciations of him as hypocritical and self-serving. And Disraeli's inmost thoughts may indeed have been as his critics describe them but it is his pronouncements and policies when in power that influenced events so it is to those that we must look. Given the discrimination against Jews of his day, he may in his heart have despised the English people but it was his proclaimed love of them that got results. And his proclamation of the Tories as the party that cared about the nation as a whole rather than sectional interests (the "One nation" claim) was at the least clever, no matter how it was motivated. And no-one has ever doubted Dizzy's cleverness.

At one of the great international political conferences of the time (Berlin Congress of 1878), Germany was represented by Bismarck and Britain by Disraeli. To Britain's considerable benefit, Disraeli ran rings around all of them -- causing Bismarck to make his famous admiring remark: "Der alte Jude. Das is der Mann" ("The old Jew. THAT is the man"). Coming from Bismarck, that was a compliment indeed. Disraeli himself attributed the greater social peace of 19th century England to Englishness but to a considerable extent it was also his own personal achievement.

I am always a bit amused at how well Disraeli's propaganda has lasted. Although the idea was NOT original to him, it is mainly Disraeli whom we have to thank for rebranding the British Tories in the 19th century as the "Conservatives". And the reason Disraeli did that is a very modern and rather clever one. Disraeli and the Tories did indeed want to conserve SOME things from traditional British ways and customs but, under Disraeli's leadership, the Tories ALSO became a great party of reform. As already mentioned, it was Disraeli who introduced some of Britain's first worker protection laws and who extended the vote to many working class people who had never had it before. So Disraeli chose a name that was certainly accurate in one respect but which also disguised another major part of his agenda -- which was CHANGE! He named his party in a way that deflected attention from its belief in the need for change in certain areas -- in order to confuse his opponents and reassure his allies. Communists do something similar when they label their governments as "Democratic".

So why did Disraeli lead the Tories so far down the road of reform? Basically because he saw that the pressure to give the vote to the workers would in the end be irresistible. There had long been agitation for it and that agitation was getting ever more energetic. So what he wanted to do was to avoid another French Revolution. He wanted the transition to majority rule to be peaceful, orderly, non-destructive and non-tyrannical. He succeeded brilliantly. He succeeded in moving the Tories away from being a party of the rich to being a party for all Englishmen and he rightly saw that working class Englishmen could be relied on for patriotism and good sense just as well as more prosperous Englishmen could be. And that is true to this day.

So while it is true that Disraeli wanted to conserve what was best from the past, conserving anything was for him primarily a means to an end. And if that end needed reform to achieve it, that was fine too. So what was he aiming at achieving by his reforms? What WAS the end he was aiming at? Unlike Leftists, he was not aiming at equalizing everybody or creating the worker-led tyranny that his contemporary, Karl Marx, was advocating. He was aiming at the opposite of that. He wanted to preserve civility and avoid tyranny. He wanted people to be free to get on with their lives in their own accustomed way without interference from other people or from the State. He attached himself to that great tradition in English politics that values individual liberty and suspects the State. And that tradition goes back a long way in England -- right back to the time when Britannia became England about 1500 years ago. The advocates of the individual versus the collectivity have not always been called conservatives but in England they have always been there -- as I will set out at length in the rest of this article.

Leftists, of course, have always been happy to misrepresent conservatism as resistance to ALL change -- something that all conservative thinkers that I know of explicitly reject -- including both Edmund Burke and Disraeli (as we shall see) -- but even conservative intellectuals these days are still sometimes misled by Disraeli's old propaganda trick (see e.g. here or here) and assume that the PRIME aim of conservatives is to conserve -- but in so doing they simply show their ignorance of history. There are only SOME things that conservatives want to conserve and those things that conservatives do want to conserve they want to conserve for a reason, not as an end in itself. And the end they seek is safety and liberty for the individual to live his own life in his own way with minimal interference from others and from the State. They realize that the State and society generally are sometimes needed to secure that freedom but do not lose sight of the fact that freedom for the individual is the end of political policy, not an optional extra. And present day politics are much like the politics of Disraeli's day. Conservatives don't want to conserve our disastrous educational and social welfare systems, they want to reform them. And they want to reform them by empowering the individual -- just as conservatives have always done.

The most loved and most influential conservative leader of the 20th century knew what conservatism was about, of course. He said: "If you analyze it I believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism..... The basis of conservatism is a desire for less government interference or less centralized authority or more individual freedom". And if Ronald Reagan did not know what conservatism was all about, who would?

Although the term "conservatism" first acquired a political use in the 19th century, that does not of course mean that thinking now generally called conservative arose for the first time in that era. Political labels come and go and ideas that are at one time associated with one political party can at a later time come to be associated with another party. It is my basic thesis in this article, however, that there has long been an important polarity in politics that has survived the comings and goings of political parties and I aim to trace that polarity through history at some length. As a matter of historical interest, however, I set out below a potted history of the term "conservatism", which I owe to Martin Hutchinson, author of Great Conservatives:

"The etymology of Conservatism is straightforward. The term was first used as a description of a political party in a 50 page article, probably by John Wilson Croker, in the January 1830 Quarterly Review, a publication that generally supported the great Tory governments of 1783-1830, then in their last months of power before losing definitively to the Whigs in November of that year. The "Conservative" party was indeed the party that sought to preserve what was already there; in this case the specific constitution and policies of those Tory governments, which were by that time embattled.

After the series of Tory disasters in 1830-32, the term "Conservative" was picked up by Sir Robert Peel, leader of the Tory remnants, and was used to do three things. First, it was used to reassure traditionalist voters that the party was opposed to further destructive change. Second, it was used to give the party a "new image" that might appeal to moderates. Third, by stigmatizing them as not "Conservatives" but "reactionaries" it was used to de-legitimize the remnants of the Tory right, such as the Duke of Wellington and more distantly the aged Lord Eldon, who were a threat to Peel's dominance.

By the time Disraeli became leader of the Conservative Party in 1868, the term had been in use for nearly two generations. It had been set aside after the 1846 split over the Corn Laws, when the party divided into "Peelites" and "Protectionists" but had been brought back into full use by Disraeli's predecessor as leader, the 14th Earl of Derby, after Peel died in 1850 and the party abandoned protectionism in 1852".

But it was Disraeli who was by far the most eloquent advocate of the virtues of conservatism and it was he who is generally credited with bringing the term into common use as the name of his party. How much of Disraeli's often-expressed sentimental attachment to almost everything traditionally English was propaganda and how much was sincerely felt, we can really only speculate but that his deeds served the preservation of English liberty and civility well there can be no doubt. There were none of the big 19th century upheavals in England that there were in Europe. Calling on the accumulated wisdom of English traditions to both guide and limit reform was certainly a practical, popular and political success.

This is not the place for a full discussion of the many huge social and economic changes that took place in the 19th. century, so I have contented myself with a quick mention of just Disraeli and Bismarck. Those two do not remotely, however, exhaust the list of interesting conservatives from that time. There were in fact many conservatives of the time who acted in ways that upset stereotypes popular today. A good place to start exploration of that would probably be any history of the life and works of Richard Oastler. He was a notable predecessor of Disraeli in worker-welfare agitation and legislation yet was also, like Disraeli, a high Tory. By modern standards he would be the most hopeless reactionary yet he was also a passionate and effective advocate for the welfare of the workers. History is very good at overturning simple theories! And I think it should already be clear that the concept of conservatism as opposition to change is one of the silliest of all theories.

I might note at this stage that this article is not intended as a simple chronology (there are already plenty of political histories that do that) but rather as the development of an argument, so for the purposes of that argument I will skip back and forth through history to some extent. For that reason I will not say any more about Disraeli and the 19th century at this stage but we will meet him on several occasions below. See for example here and here. I might also mention that this article is intended as a survey of the facts rather than as a statement of my personal beliefs. For anybody who is interested in what my personal views on political matters might be, there is a brief summary of that here.

Military Dictators?

In the late 20th century, it was a common rhetorical ploy of the more "revolutionary" Left in the "Western" world simply to ignore democracy as an alternative to Communism. Instead they would excuse the brutalities of Communism by pointing to the brutalities of the then numerous military dictatorships of Southern Europe and Latin America and pretend that such regimes were the only alternative to Communism. These regimes were led by generals who might in various ways be seen as conservative (though Peron was undisputably Leftist) so do they tell us anything about conservatism?

Historically, most of the world has been ruled by military men and their successors (Sargon II of Assyria, Alexander of Macedon, Caesar, Augustus, Constantine, Charlemagne, Frederick II of Prussia etc.) so it seems unlikely but perhaps the main point to note here is that the Hispanic dictatorships of the 20th century were very often created as a response to a perceived threat of a Communist takeover. This is particularly clear in the case of Spain, Chile and Argentina. They were an attempt to fight fire with fire. In Argentina of the 60s and 70s, for instance, Leftist "urban guerillas" were very active -- blowing up anyone they disapproved of. The nice, mild, moderate Anglo-Saxon response to such depredations would have been to endure the deaths and disruptions concerned and use police methods to trace the perpetrators and bring them to trial. Much of the world is more fiery than that, however, and the Argentine generals certainly were. They became impatient with the slow-grinding wheels of democracy and its apparent impotence in the face of the Leftist revolutionaries. They therefore seized power and instituted a reign of terror against the Leftist revolutionaries that was as bloody, arbitrary and indiscriminate as what the Leftists had inflicted. In a word, they used military methods to deal with the Leftist attackers. So the nature of these regimes was only incidentally conservative. What they were was essentially military. We have to range further than the Hispanic generals, therefore, if we are to find out what is quintessentially conservative.

It might be noted, however, that, centuries earlier, the parliamentary leaders of England -- led by Fairfax, Cromwell etc. -- did something similar to the Hispanic generals of the 20th century. Faced by an attempt on the part of the Stuart tyrant to abrogate their traditional rights, powers and liberties, they resorted to military means to overthrow the threat. There is no reason to argue that democracy cannot or must not use military means to defend itself or that Leftists or anyone else must be granted exclusive rights to the use of force and violence.

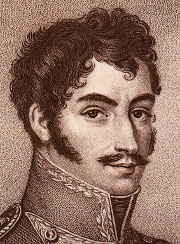

It might also be noted that the Hispanic generals were operating within a very different tradition. The abiding hero of Latin America is Simon Bolivar, the great liberator. But the ideas about government put forward by Bolivar were very authoritarian -- ideas about how the masses need to be "educated" and generally dominated by a self-chosen elite -- ideas that put Bolivar in the company of men like Mussolini and Lenin -- ideas that are totally outside the democratic traditions of Anglo-Saxon conservatism. Excerpt:

"Education was also touched upon by Simon Bolivar, especially in his Essay on Public Education, as a tool for governments to re-educate their citizens to the responsibilities and duties of participation in public life. Bolivar also commented on the weaknesses and limits of liberal democracy when writing to explain the necesity of a strong, republican form of government.... Spanish American people required that their new states be organized in such a way as to maintain order by checking the popular forces until they could be trained in the civic virtues. Bolivarism emphasizes the common good over the individual"The Hispanic generals were doing very little more than putting Bolivarism into practice and Bolivarism was certainly not conservatism.

Remote Historic Origins

It is a common claim that conservatism, as we now know it in the English-speaking world, originated with the Anglo/Irish parliamentarian Edmund Burke (of whom more anon) at the time of the French revolution. What Burke (1790) himself said is the opposite of that, however. He saw what he was defending as stretching far back into English history -- and an updated version of that type of thinking is presented here.

My submission is that the modern-day conservatism of the English-speaking world is a survival into modern times of an ancient human tradition that the English inherited from their Germanic ancestors -- the invaders (Angles and Saxons) from coastal Germany who overran Romano-Celtic Britannia around 1500 years ago and made it into England. They brought with them a very decentralized, consultative, largely tribal system of government that was very different from the Oriental despotisms that had ruled the civilized world for most of human history up to that time. And they liked their decentralized, consultative system very much. So much so that the system just kept on keeping on in England, century after century, despite many vicissitudes. Only the 20th century really shook it. So conservatism in English-origin countries is simply Anglo-Saxon traditional values.

The curious thing, of course, is that similar values were also observable in ancient Greece and Rome and may even have been what underlay the city-states of the original human civilization in Mesopotamia. The affinity of the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic people for democracy is certainly very reminiscent of ancient Greek democracy and the early Roman republic and, in turn, the city-states that characterized ancient Greece and Rome are very reminiscent of ancient Mesopotamia. What appears to have happened is that the human race has a great tendency towards centralization of government -- seen vividly in the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt, in the bureaucratic states of pre-modern China, in various Babylonian, Assyrian, Persian, Roman, Moghul and Ottoman empires, in the Kings of Mediaeval Europe and in the vast swathe of communist bureaucracies in the 20th century. And this centralizing tendency almost always seems to triumph over an even earlier tendency towards respect for the individual and a form of government that is directly responsive in some way to the popular will. And it is that very early tradition that only the Anglo-Saxons -- and their close relatives in Scandinavia and the Netherlands -- have carried forward into the modern world. Only among the Anglo-Saxons and their close relatives did the power of centralism never quite succeed in squashing human dreams for responsive, respectful and representative government. And it is this dream that conservatives of the English-speaking world carry forward today.

My thesis here is, of course, not exactly original. Montesquieu, De Tocqueville and even Thomas Jefferson all saw English exceptionalism and independence of spirit as tracing back to German roots and all harked back to Tacitus for their view of the early German character. If I was mischievous, I suppose I could have called this article "Jefferson Revisited", or some such. The work of Macfarlane (1978 & 2000) is however probably the best modern reference on the topic.

But let us look at what Tacitus said about the early Germans that he knew around 2000 years ago. Excerpts:

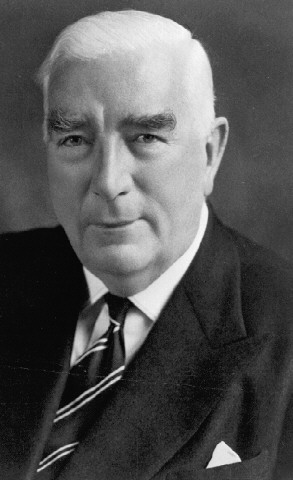

Publius Cornelius Tacitus

They choose their kings by birth, their generals for merit. These kings have not unlimited or arbitrary power, and the generals do more by example than by authority.

About minor matters the chiefs deliberate, about the more important the whole tribe. Yet even when the final decision rests with the people, the affair is always thoroughly discussed by the chiefs. They assemble, except in the case of a sudden emergency, on certain fixed days, either at new or at full moon; for this they consider the most auspicious season for the transaction of business. Instead of reckoning by days as we do, they reckon by nights, and in this manner fix both their ordinary and their legal appointments. Night they regard as bringing on day. Their freedom has this disadvantage, that they do not meet simultaneously or as they are bidden, but two or three days are wasted in the delays of assembling. When the multitude think proper, they sit down armed. Silence is proclaimed by the priests, who have on these occasions the right of keeping order. Then the king or the chief, according to age, birth, distinction in war, or eloquence, is heard, more because he has influence to persuade than because he has power to command. If his sentiments displease them, they reject them with murmurs; if they are satisfied, they brandish their spears.